turtles and tortoises

Shelled Evolutionary Wonders Face Threats in the Modern Era

More than half of all turtle and tortoise species are at risk of extinction, making them one of the most threatened vertebrate groups.

These shelled evolutionary wonders play important roles to keep their ecosystems healthy. Tortoises and freshwater turtles are important seed and spore dispersers for many plants, trees and fungi. Snapping and softshell turtles are important scavengers that help maintain clean aquatic ecosystems. Burrows dug by some tortoise species are critical refuges from heat, cold and fire for numerous other animal species.

Alarmingly, seven species of tortoises have gone extinct in recent history, and of the remaining 366 species of turtles and tortoises, more than half are facing extinction.

While turtles and tortoises have evolved to keep a few steps ahead of the extinction risks posed by predators, severe weather and disease for 225 million years, humans have proven to be their most profound threat.

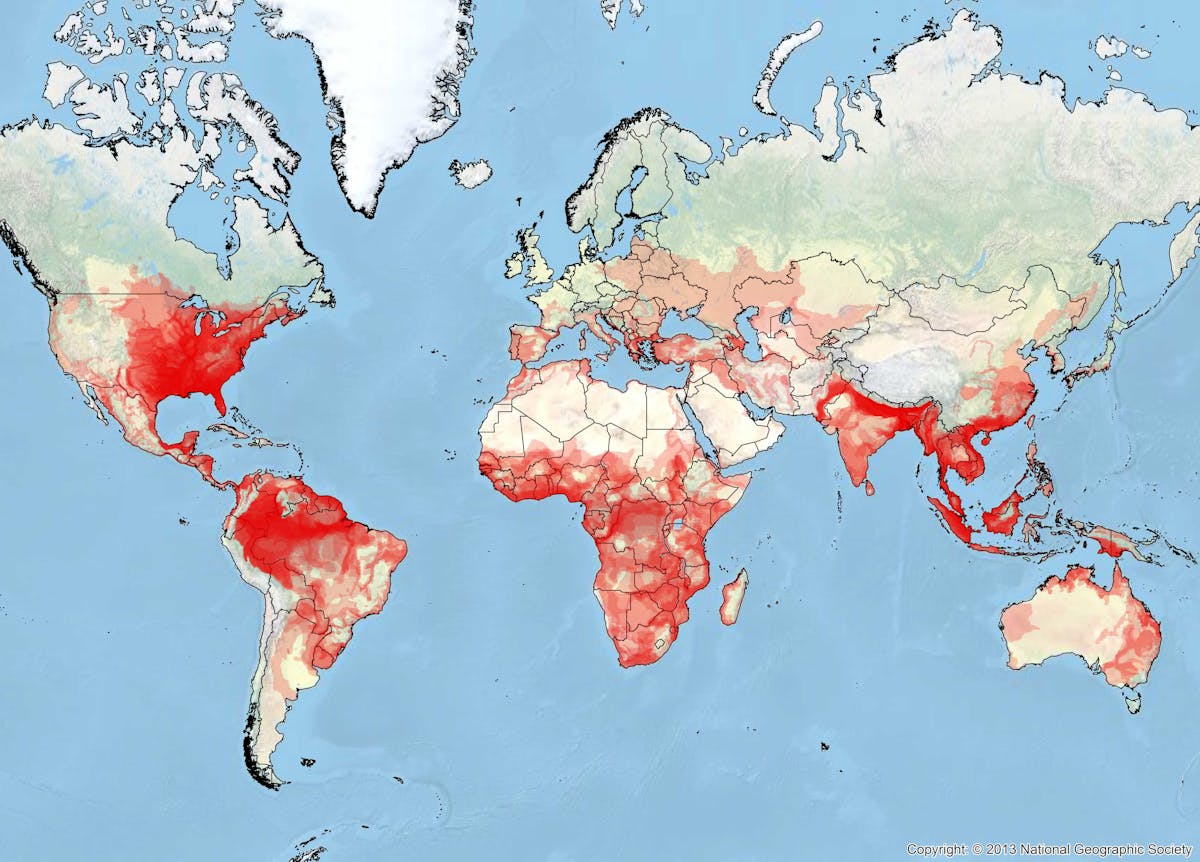

Humans have altered, destroyed and polluted tortoise and freshwater turtle habitats and spread diseases that threaten their populations. However, there are still habitats that can support large numbers of turtles and tortoises, and even relatively small areas can support thriving turtle populations if they are effectively protected. Scientists have identified 16 priority areas around the world that are home to a wide diversity of tortoises and freshwater turtles. If adequate habitats within those regions were protected, it would significantly help the turtles’ chances of survival.

For millennia, people have decimated tortoise and turtle populations by collecting and trading them for food, pets and medicinal use–both legally and illegally. According to scientists, the single most important thing that would help tortoises and turtles immediately is ending unsustainable trade and illegal wildlife trade.

Between 2000 and 2015, more than 300,000 tortoises and freshwater turtles were seized from the illegal wildlife trade. Since turtles and tortoises are long-lived and slow-growing species, they can’t reproduce fast enough to replenish their populations when such large numbers are taken from the wild.

Re:wild works with the Turtle Conservancy, IUCN and other global and local organizations to protect and restore the world’s tortoises and freshwater turtles. Together, we:

Protect habitat for Critically Endangered tortoises and freshwater turtles

Research the distribution, natural history, population status and conservation needs of turtle species and publish the results in technical publications and in public outreach, such as the Checklist and Atlas of Turtles of the World

Support the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species to assess the conservation status of every species of tortoise and freshwater turtle, which helps conservationists prioritize, manage and rewild imperiled species

Monitor and analyze legal and illegal trade and using this information to help develop policies that combat poaching and illegal trade at local, national and international (CITES) levels

Support on-the-ground turtle conservation by local scientists, conservationists and educators

The primary freshwater turtle and tortoise species Re:wild is trying to save and protect are: Swinhoe’s Giant Softshell Turtle, Geometric Tortoise, Bolson’s Tortoise, and Fernandina Galápagos Tortoise.

Swinhoe’s Giant Asian Softshell Turtle (Vietnam and China)

Swinhoe’s Giant Asian Softshell Turtle is one of the largest freshwater turtles in the world, weighing up to 260 pounds. Only four known individuals of this species exist, including a male in captivity in China at the Suzhou Zoo, and three turtles in different lakes in Vietnam. A coalition, led by The Asian Turtle Program of Indo-Myanmar Conservation, including Re:wild, searched for more individuals in Vietnam to give the species another chance at breeding and escaping extinction. The Asian Turtle Program has successfully identified three individuals in Vietnam and in 2020 identified one of them as a female.

Geometric Tortoise (South Africa)

The Geometric Tortoise is one of the most imperiled turtle species in the world. Originally widespread in the lowland Fynbos habitat of the Western Cape province of South Africa, its habitat has been turned into vineyards, orchards and wheat fields, causing the population to decline and eventually collapse.

The Turtle Conservancy and the Southern Africa Tortoise Conservation Trust, with support from Re:wild, stepped in to purchase one of the very few remaining habitat patches where these tortoises still thrive. With a dedicated preserve for the tortoise, we now focus on keeping the habitat protected from invasive plants and wildfires, recovering the tortoise population and researching the species.

Bolson Tortoise (Mexico)

Re:wild closely supports the Turtle Conservancy and the Mexican NGO HABIO, A.C., to protect the Bolson Tortoise in its habitat in Mexico.

The centerpiece of those efforts is the 62,000 acre Bolson Tortoise Ecosystem Preserve (BTEP) in the Bolson de Mapimí Biosphere Reserve in northern Mexico. The preserve was established in 2016 and expanded in 2019 and encompasses some of the healthiest remaining groups of Bolson Tortoises living in the wild.

Beyond the Mapimí Biosphere Reserve, this species once ranged throughout the grasslands of the Chihuahuan Desert wilderness, but has now effectively disappeared due to overexploitation and its habitat being turned into farmland. Our work at the Preserve focuses on keeping cattle out of the tortoise’s habitat, rewilding native plants and engaging the local community. Complementary work by our colleagues at the Turner Endangered Species Fund aims to eventually return these tortoises to other historical locations.

Fernandina Galápagos Tortoise (Ecuador)

The Giant Tortoise of Fernandina Island in the Galápagos was known from a single male specimen collected in 1906 and described in 1914. In the decades that followed, tantalizing clues suggested that there may still be Fernandina Galapagos Tortoises on the island, but it was not until February 2019 that a second tortoise was found on Fernandina island. The original male specimen is one of the most extreme saddleback tortoises ever seen, yet the female found recently doesn’t show the expected matching saddleback shape. Scientists are using genetic testing to clarify which species she is. Regardless of her ancestry, the island of Fernandina, which is the youngest and volcanically most active island in Ecuador’s Galápagos archipelago, deserves more tortoise surveys and conservation support for its remarkable biodiversity.