Lost Fishes

All around the world, freshwater fish face multiple stressors that have caused populations to plummet and, for all kinds of reasons, once discovered species have fallen off our radar. These lost fishes are species that have gone unseen for years – even decades – and some are feared possibly extinct. In order to save these species, we first need to find them.

Working with Shoal, we have launched a freshwater fish-focused initiative to our successful Search for Lost Species campaign. In collaboration with Shoal and the IUCN-SSC Freshwater Fish Specialist Group, we have compiled a list of more than 300 fish species that are currently missing to science.

Annamite Barb

Diyarbakir (Batman River) Loach

Duck-Billed Buntingi

Spinach Pipefish

Leopard Barbel

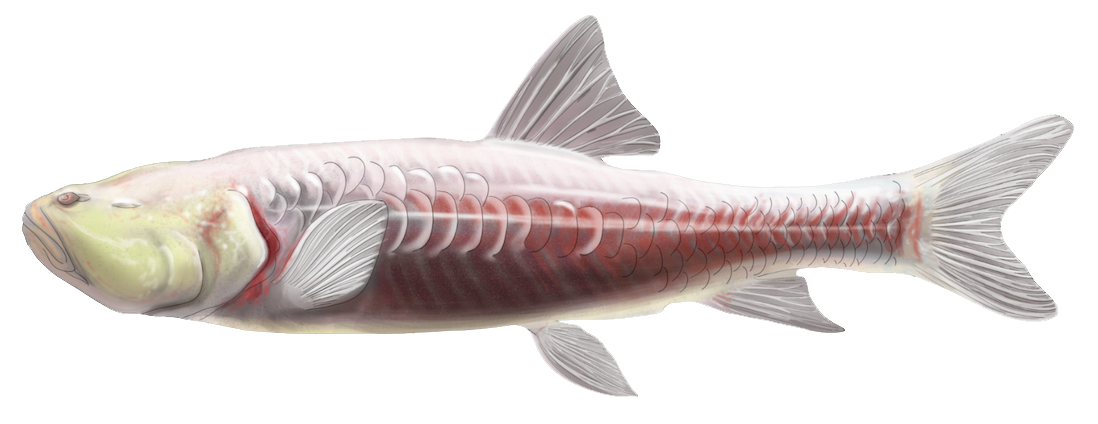

Syr Darya Shovelnose Sturgeon

Titicaca Orestias

Haditha Cavefish

Itasy Cichlid

Fat Catfish

Explore More About Lost Species

Continue your journey to learn how lost species are found, why they disappear, and the full scope of our search efforts.