Lost Harlequin Toads

Our most wanted lost harlequin toads include species that have been lost to science for at least a decade (and often for much longer!) and, like our most wanted lost species, may be lost for a variety of reasons. We worked with the Atelopus Survival Initiative to determine this list of lost harlequin toads. They represent a broad geographical reach across harlequin toads’ range in the Neotropics, and may present opportunities for inspiring conservation action. Read more about Re:wild's harlequin toad conservation efforts.

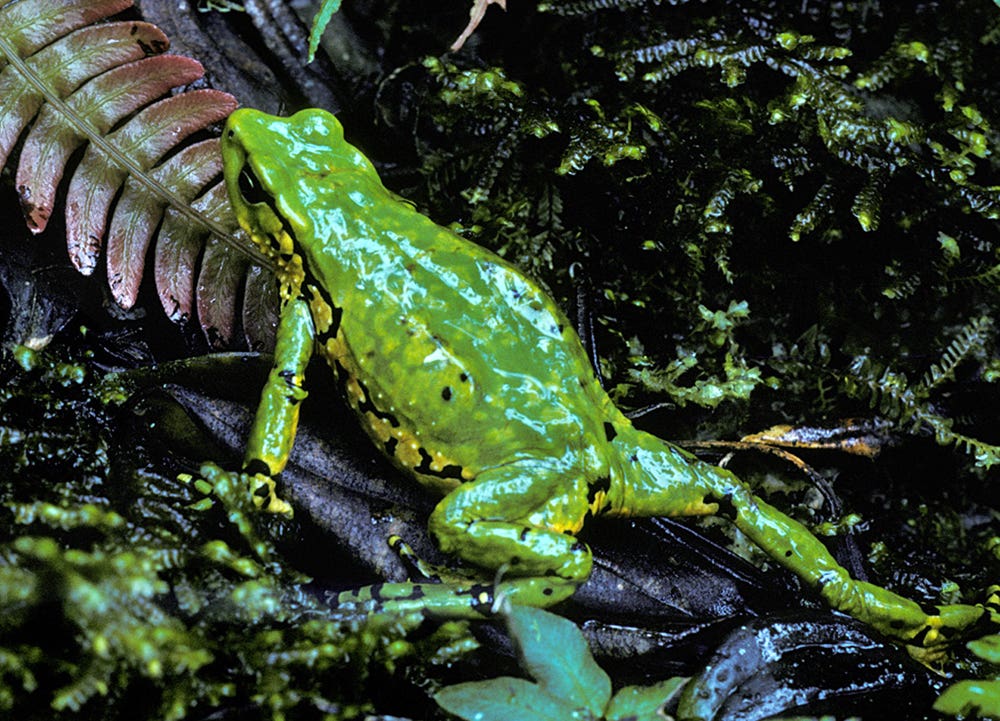

Angelito Harlequin Toad

Scientific Name: Atelopus angelito

Last Seen: 2000 in Colombia

Years Lost: 24

Red List Status: Critically endangered

The Angelito Harlequin Toad is the same classic pea green as Kermit the Frog, but with deep brown eyes lined with yellow. They live in both cloud forests and scrubby bush lands along streams. This species is known from only a handful of individuals in two regions—one in Ecuador and one in Colombia. Though their name literally translates to “little angel Atelopus,” it actually comes from their discoverer, Miguel Angel Barrera.

Because the species has not been included in molecular phylogenetic studies, scientists are still unsure of its exact place in the Atelopus family tree, but evidence points to it being very similar to the Malvasa Harlequin Toad (A. eusebianus) and the Huila Harlequin Toad (A. ebenoides), both of whom are also lost toads and classified as Critically endangered (possibly extinct). The Angelito Harlequin Toad was last seen in the wild in 2000. So little is known about the species that the cause of its decline is unverified but is likely to be related to chytrid fungus, as with many other harlequin toads. Other threat factors may include habitat loss, water pollution, and invasive species.

Photo: Doug Wechsler

Last Seen: 2000 in Colombia

Years Lost: 24

Red List Status: Critically endangered

The Angelito Harlequin Toad is the same classic pea green as Kermit the Frog, but with deep brown eyes lined with yellow. They live in both cloud forests and scrubby bush lands along streams. This species is known from only a handful of individuals in two regions—one in Ecuador and one in Colombia. Though their name literally translates to “little angel Atelopus,” it actually comes from their discoverer, Miguel Angel Barrera.

Because the species has not been included in molecular phylogenetic studies, scientists are still unsure of its exact place in the Atelopus family tree, but evidence points to it being very similar to the Malvasa Harlequin Toad (A. eusebianus) and the Huila Harlequin Toad (A. ebenoides), both of whom are also lost toads and classified as Critically endangered (possibly extinct). The Angelito Harlequin Toad was last seen in the wild in 2000. So little is known about the species that the cause of its decline is unverified but is likely to be related to chytrid fungus, as with many other harlequin toads. Other threat factors may include habitat loss, water pollution, and invasive species.

Photo: Doug Wechsler

Baldias Harlequin Toad

Scientific Name: Atelopus sernai

Last Seen: 2001 in Colombia

Years Lost: 23

Red List Status: Critically endangered

Only ever known from two, or perhaps three locations, the Baldias Harlequin Toad was likely never a common species. A dappled green-and-black harlequin toad, it was originally discovered along forest borders high in the Andean mountains of Colombia.

Recent surveys have not found evidence of the species; the last individual was located in 2001. Another individual may have been photographed in 2009, but the image has not been confirmed. Invasive predatory trout and agricultural pollution both pose a threat to this species, along with chytrid fungus and climate change. Photo: Luis G. Olarte

Last Seen: 2001 in Colombia

Years Lost: 23

Red List Status: Critically endangered

Only ever known from two, or perhaps three locations, the Baldias Harlequin Toad was likely never a common species. A dappled green-and-black harlequin toad, it was originally discovered along forest borders high in the Andean mountains of Colombia.

Recent surveys have not found evidence of the species; the last individual was located in 2001. Another individual may have been photographed in 2009, but the image has not been confirmed. Invasive predatory trout and agricultural pollution both pose a threat to this species, along with chytrid fungus and climate change. Photo: Luis G. Olarte

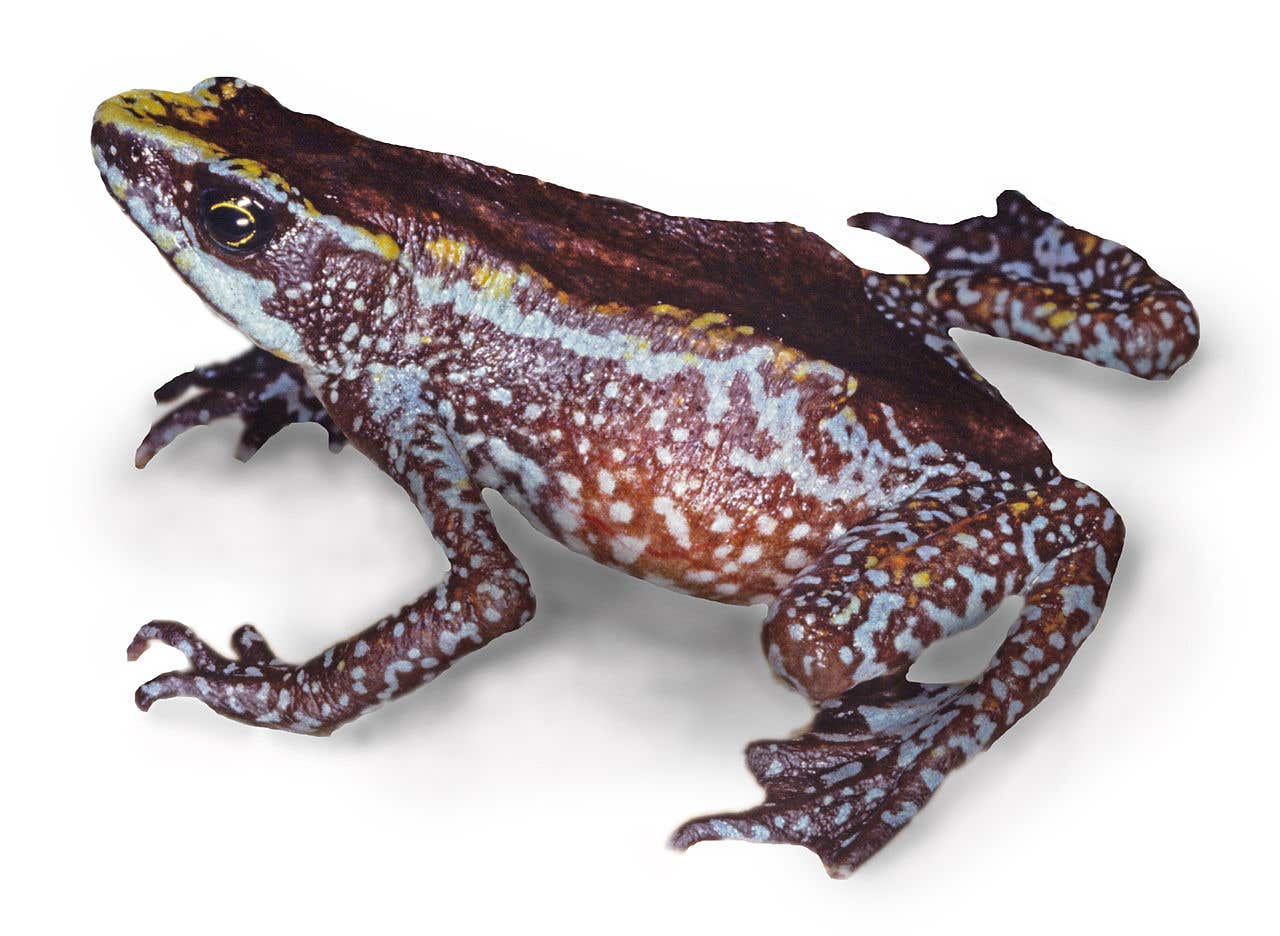

Boyaca’s Painted Harlequin Toad

Scientific Name: Atelopus marinkellei

Last Seen: 2006 in Colombia

Years Lost: 18

Red List Status: Endangered

A dark harlequin toad bedecked with bright contrasting patches; the Boyaca’s Painted Harlequin Toad has already been rediscovered once—but has since disappeared again. It is native to streams in high montane ecosystem of the Colombian Andes, where it prefers to spend its time tucked into fallen leaves.

The species was common until about 1995, when their population numbers dropped precipitously. One individual was found in 2004. Two—one of them dead—were found in 2006. Since then, despite recent search efforts, no surviving Boyaca’s Painted Harlequin Toads have been sighted. Like other harlequin toad species, chytrid fungus is likely the cause of its demise, along with climate change.

Photo: Carlos Frederico Duarte Rocha

Last Seen: 2006 in Colombia

Years Lost: 18

Red List Status: Endangered

A dark harlequin toad bedecked with bright contrasting patches; the Boyaca’s Painted Harlequin Toad has already been rediscovered once—but has since disappeared again. It is native to streams in high montane ecosystem of the Colombian Andes, where it prefers to spend its time tucked into fallen leaves.

The species was common until about 1995, when their population numbers dropped precipitously. One individual was found in 2004. Two—one of them dead—were found in 2006. Since then, despite recent search efforts, no surviving Boyaca’s Painted Harlequin Toads have been sighted. Like other harlequin toad species, chytrid fungus is likely the cause of its demise, along with climate change.

Photo: Carlos Frederico Duarte Rocha

Camouflaged Harlequin Toad

Scientific Name: Atelopus simulatus

Last Seen: 2003 in Colombia

Years Lost: 21

Red List Status: Critically endangered

The Camouflaged Harlequin Toad is a species that was once extremely common, but now is extremely rare—or even disappeared entirely. The species is (or was) native to the central Andean mountains in Colombia, preferring habitat in forests or grasslands near streams. Photos of the toads depict a colorful and showy black, red, and green frog with striking coloration patterns.

Before 1999, it was relatively easy to locate individuals, but since then only two sightings have been reported: one in 2001 and one in 2003. More surveys are needed to determine if the species is still surviving. It faces threats including chytrid fungus, water pollution, and habitat destruction.

Last Seen: 2003 in Colombia

Years Lost: 21

Red List Status: Critically endangered

The Camouflaged Harlequin Toad is a species that was once extremely common, but now is extremely rare—or even disappeared entirely. The species is (or was) native to the central Andean mountains in Colombia, preferring habitat in forests or grasslands near streams. Photos of the toads depict a colorful and showy black, red, and green frog with striking coloration patterns.

Before 1999, it was relatively easy to locate individuals, but since then only two sightings have been reported: one in 2001 and one in 2003. More surveys are needed to determine if the species is still surviving. It faces threats including chytrid fungus, water pollution, and habitat destruction.

Chiriqui Harlequin Toad

Scientific Name: Atelopus chiriquiensis

Last Seen: 1996 in Costa Rica

Years Lost: 28

Red List Status: Critically endangered

Native to the wet, cool cloud forests of the Talamanca Mountains in Costa Rica to Panama, Chiriqui Harlequin Toads once came in a range of colors, with the females differing dramatically from the males. Males ranged from yellow and green to brown, often with black patches along their backs. Females often had a flame-colored stripe, outlined in black, running from their noses along their sides. Both sexes had orange or green eyes (sometimes even one eye of each color) with gold irises. The Chiriqui Harlequin Toad lived along mountain forest streams. Females tended to prefer shaded forests, while the males stayed closer to the streams. Females visited the wetter areas for breeding. Before their population declined, they were usually very abundant in their habitat.

Over the course of three generations, 80–100 percent of the population disappeared, mainly due to disease. They were last seen in the wild in 1996. Habitat loss, climate change, and the introduction of predatory trout may also have contributed to their decline and subsequent extinction.

Photo: Brian Gratwicke, Smithsonian Conservation Biology Center

Last Seen: 1996 in Costa Rica

Years Lost: 28

Red List Status: Critically endangered

Native to the wet, cool cloud forests of the Talamanca Mountains in Costa Rica to Panama, Chiriqui Harlequin Toads once came in a range of colors, with the females differing dramatically from the males. Males ranged from yellow and green to brown, often with black patches along their backs. Females often had a flame-colored stripe, outlined in black, running from their noses along their sides. Both sexes had orange or green eyes (sometimes even one eye of each color) with gold irises. The Chiriqui Harlequin Toad lived along mountain forest streams. Females tended to prefer shaded forests, while the males stayed closer to the streams. Females visited the wetter areas for breeding. Before their population declined, they were usually very abundant in their habitat.

Over the course of three generations, 80–100 percent of the population disappeared, mainly due to disease. They were last seen in the wild in 1996. Habitat loss, climate change, and the introduction of predatory trout may also have contributed to their decline and subsequent extinction.

Photo: Brian Gratwicke, Smithsonian Conservation Biology Center

Flat-Spined Harlequin Toad

Scientific Name: Atelopus planispina

Last Seen: 1987 in Ecuador

Years Lost: 37

Red List Status: Critically Endangered

The Flat-Spined Harlequin Toad is a green with large black splotches along its back, and the backs of its limbs. Tiny spines cover its body, especially its flanks, giving it its name. It has yellow-green eyes and green foot pads, distinguishing it from other similar species. Native to the eastern foothills of the Ecuadorean Andes, this toad prefers shrubby forests near streams at elevations of between 1,000 and 2,000 meters, though it has also been found in grasslands and forest fragments. Like its relatives, it lives almost exclusively near streams.

It was last spotted in 1987 and has not been seen since, despite some surveys. Even then, it was thought the population had experienced a drastic decline and fewer than 50 individuals survived. The species faces threats including chytrid fungus, and deforestation as the result of agriculture, mining and other development. Only about half of the habitat within its natural range remains intact, though fortunately some of its habitat is encompassed by a protected area.

Photo: Luis A. Coloma, Centro Jambatu de Investigación y Conservación de Anfibios

Last Seen: 1987 in Ecuador

Years Lost: 37

Red List Status: Critically Endangered

The Flat-Spined Harlequin Toad is a green with large black splotches along its back, and the backs of its limbs. Tiny spines cover its body, especially its flanks, giving it its name. It has yellow-green eyes and green foot pads, distinguishing it from other similar species. Native to the eastern foothills of the Ecuadorean Andes, this toad prefers shrubby forests near streams at elevations of between 1,000 and 2,000 meters, though it has also been found in grasslands and forest fragments. Like its relatives, it lives almost exclusively near streams.

It was last spotted in 1987 and has not been seen since, despite some surveys. Even then, it was thought the population had experienced a drastic decline and fewer than 50 individuals survived. The species faces threats including chytrid fungus, and deforestation as the result of agriculture, mining and other development. Only about half of the habitat within its natural range remains intact, though fortunately some of its habitat is encompassed by a protected area.

Photo: Luis A. Coloma, Centro Jambatu de Investigación y Conservación de Anfibios

Scarlet Harlequin Toad

Scientific Name: Atelopus sorianoi

Last Seen: 1990 in Venezuela

Years Lost: 34

Red List Status: Critically Endangered

The rediscovery of this lost toad could be the key to better understanding how species rebound from the chytrid fungus that has decimated amphibians worldwide and hit harlequin toads particularly hard. The Scarlet Harlequin Toad has the most restricted geographic range of any Venezuelan Atelopus species and is known from a single stream in an isolated Venezuelan cloud forest.

Last Seen: 1990 in Venezuela

Years Lost: 34

Red List Status: Critically Endangered

The rediscovery of this lost toad could be the key to better understanding how species rebound from the chytrid fungus that has decimated amphibians worldwide and hit harlequin toads particularly hard. The Scarlet Harlequin Toad has the most restricted geographic range of any Venezuelan Atelopus species and is known from a single stream in an isolated Venezuelan cloud forest.

Onore’s Harlequin Toad

Scientific Name: Atelopus onorei

Last Seen: 1990 in Ecuador

Years Lost: 34

Red List Status: Critically Endangered

Boasting blazing blue eyes and named more than 15 years after it was lost, the Onore’s Harlequin Toad is native to the Pacific side of the Andes in Ecuador. Onore’s Harlequin Toad is known from only two fast-moving mountain streams. It was last seen in the wild in 1990. In 2007, scientists determined that it was a separate species from the Azuay Stubfoot Toad, A. bomolochos. Onore’s Harlequin Toads are gold with green patches along their back and slightly wrinkly skin along their throats. They owe their name to Giovanni Onore, an influential and passionate scientist, previously a curator at Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador.

Onore’s Harlequin Toads are Critically Endangered (Possibly Extinct), with their population threatened by chytrid fungus, habitat destruction, introduced predators, and climate change. Their small range has no protection, and more surveys into their territory are needed.

Photo: Luis A. Coloma, Centro Jambatu de Investigación y Conservación de Anfibios

Last Seen: 1990 in Ecuador

Years Lost: 34

Red List Status: Critically Endangered

Boasting blazing blue eyes and named more than 15 years after it was lost, the Onore’s Harlequin Toad is native to the Pacific side of the Andes in Ecuador. Onore’s Harlequin Toad is known from only two fast-moving mountain streams. It was last seen in the wild in 1990. In 2007, scientists determined that it was a separate species from the Azuay Stubfoot Toad, A. bomolochos. Onore’s Harlequin Toads are gold with green patches along their back and slightly wrinkly skin along their throats. They owe their name to Giovanni Onore, an influential and passionate scientist, previously a curator at Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador.

Onore’s Harlequin Toads are Critically Endangered (Possibly Extinct), with their population threatened by chytrid fungus, habitat destruction, introduced predators, and climate change. Their small range has no protection, and more surveys into their territory are needed.

Photo: Luis A. Coloma, Centro Jambatu de Investigación y Conservación de Anfibios

Pastuso Harlequin Toad

Scientific Name: Atelopus pastuso

Last Seen: 1993 in Ecuador

Years Lost: 31

Red List Status: Critically endangered

The Pastuso Harlequin Toad is a strong, stocky toad, often yellowish or gray green in color with gray spicules along its back. It has only ever been found living on tropical mountains above the tree line, especially in damp areas. During the day, it tends to stay in the shade of vegetation or rocks. It may live—or may have lived—in close sympatry with the Angelito Harlequin Toad, especially in Ecuador.

As recently as the 1970s, the Pastuso Harlequin Toad was abundant, at least in part of its range. However, their population declined precipitously in the 1980s and 1990s. Despite intensive search efforts, the last Pastuso Harlequin Toad in Colombia was seen in 1982, and in Ecuador in 1993. Individuals have tested positive for chytrid fungus, suggesting the fungus played a role in the declines, while other threats include development, climate change, and forest fires.

Photo: Eugenia del Pino

Last Seen: 1993 in Ecuador

Years Lost: 31

Red List Status: Critically endangered

The Pastuso Harlequin Toad is a strong, stocky toad, often yellowish or gray green in color with gray spicules along its back. It has only ever been found living on tropical mountains above the tree line, especially in damp areas. During the day, it tends to stay in the shade of vegetation or rocks. It may live—or may have lived—in close sympatry with the Angelito Harlequin Toad, especially in Ecuador.

As recently as the 1970s, the Pastuso Harlequin Toad was abundant, at least in part of its range. However, their population declined precipitously in the 1980s and 1990s. Despite intensive search efforts, the last Pastuso Harlequin Toad in Colombia was seen in 1982, and in Ecuador in 1993. Individuals have tested positive for chytrid fungus, suggesting the fungus played a role in the declines, while other threats include development, climate change, and forest fires.

Photo: Eugenia del Pino

Peru Harlequin Toad

Scientific Name: Atelopus peruensis

Last Seen: 1998 in Peru

Years Lost: 26

Red List Status: Critically endangered

Last Seen: 1998 in Peru

Years Lost: 26

Red List Status: Critically endangered

Peter’s Harlequin Toad

Scientific Name: Atelopus petersi

Last Seen: 1996 in Ecuador

Years Lost: 28

Red List Status: Critically endangered

Native to the central Andean mountains in Ecuador, Peter’s Harlequin Toad has been lost since 1996. These gold-and-black toads live near streams in cloud forests and montane forests. When the toad was first discovered, it was described as being extremely common. However, in the space of a decade, the population suffered at least an 80 percent decline likely as the result of chytrid fungus, climate change, or a combination of factors. Local people say that some individuals might survive deep in the forest, and further surveys are needed. Their range at one time included the Cayambe-Coca Ecological Reserve, which gives hope that the species may not be lost forever.

Photo: Luis A. Coloma, Centro Jambatu de Investigación y Conservación de Anfibios

Last Seen: 1996 in Ecuador

Years Lost: 28

Red List Status: Critically endangered

Native to the central Andean mountains in Ecuador, Peter’s Harlequin Toad has been lost since 1996. These gold-and-black toads live near streams in cloud forests and montane forests. When the toad was first discovered, it was described as being extremely common. However, in the space of a decade, the population suffered at least an 80 percent decline likely as the result of chytrid fungus, climate change, or a combination of factors. Local people say that some individuals might survive deep in the forest, and further surveys are needed. Their range at one time included the Cayambe-Coca Ecological Reserve, which gives hope that the species may not be lost forever.

Photo: Luis A. Coloma, Centro Jambatu de Investigación y Conservación de Anfibios

Explore More About Lost Species

Continue your journey to learn how lost species are found, why they disappear, and the full scope of our search efforts.